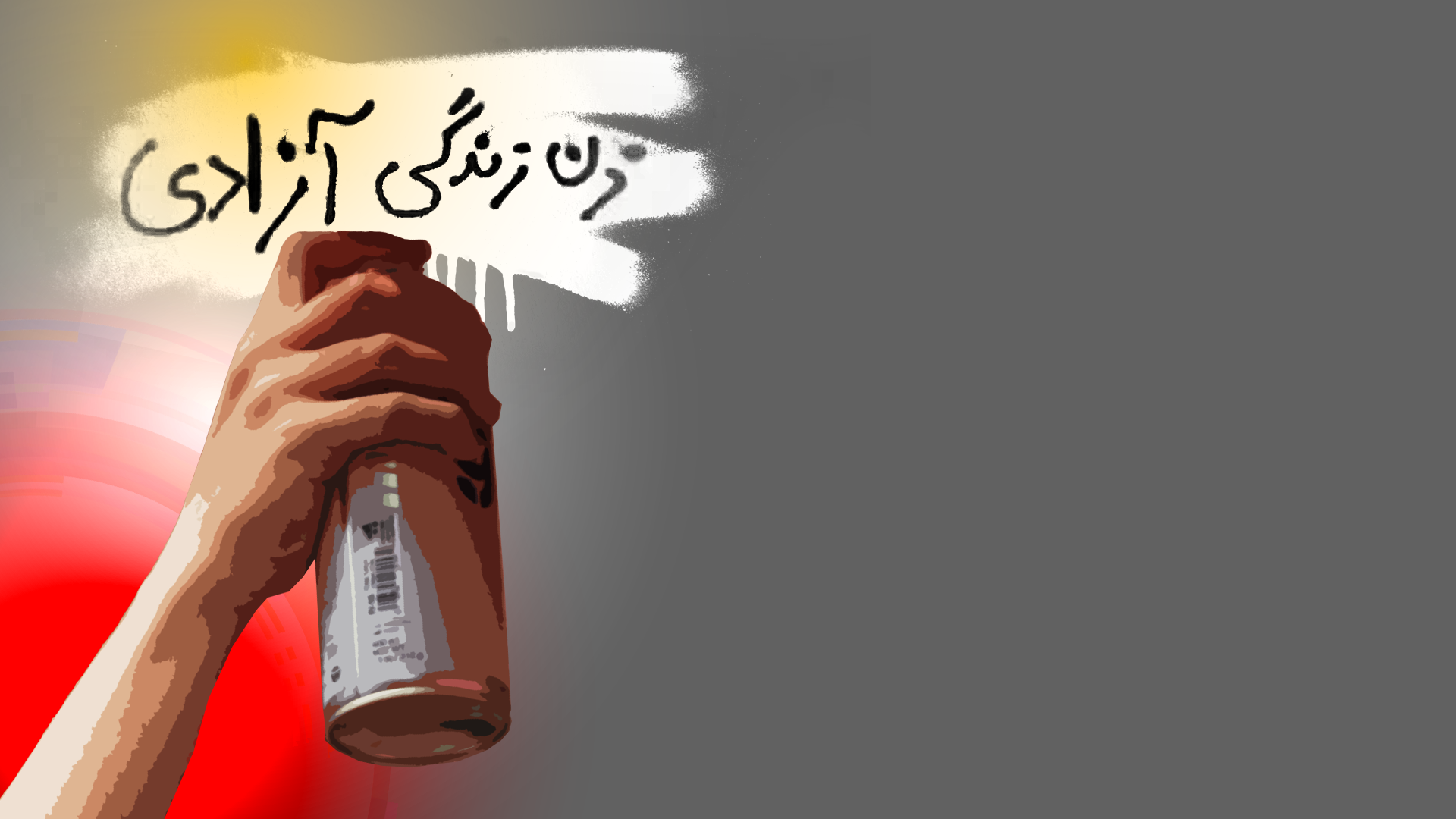

How Iranian women are defying the Islamic Republic one headscarf at a time

Nearly three years after the September 2022 killing of 22-year-old Mahsa Jina Amini ignited the largest protests in Iran’s modern history, women’s civil resistance has evolved into a sustained movement quietly but irrevocably transforming society, an extensive investigation by Iran International shows.

Drawing on 100 candid interviews with women—from religious and secular backgrounds and spanning urban centers to rural provinces—these testimonies reveal how individual acts of defiance are eroding the state’s grip and forging unexpected solidarity. Together, they point to a grassroots movement that is dismantling the state’s tools of control and exposing deep fissures in the Islamic Republic’s authority.

According to those interviewed, relatives who once enforced strict dress codes now support women who defy them, while conservative towns and even clerical families, long aligned with state ideology, are showing signs of quiet rebellion.

Despite intensified repression since the state’s brutal crackdown since the dubbed “Women, Life, Freedom” protests—including financial penalties, job losses, and expanded surveillance—women describe resistance that has become deeply personal, continuous, and increasingly beyond the state’s ability to contain. Some even now openly call for an “eye-for-an-eye” confrontation with security forces, marking a significant break from decades of largely peaceful opposition.

Conducted under constant threats of surveillance and retaliation, the interviews were arranged through underground networks, safe houses, and encrypted communications. For security reasons, the names and identifying details of all interviewees have been changed.

Breaking generational barriers

Severe restrictions for women were ushered in quickly by the Islamic Republic after it rose to power with the 1979 Revolution. Yet, the investigation shows that in the years since the Women, Life, Freedom protests, Iranian women have taken steps and often broken from previous generations, creating new forms of solidarity even within conservative and religious families.

Many women interviewed described their own homes as microcosms of state repression, with relatives enforcing the state’s Islamist ideology in deeply personal ways.

“My own father threw me out of the house,” says Sara, 26. Raised in a conservative home, Sara was expelled by her father, a judiciary official, after refusing to wear the hijab. After secretly joining protests following Mahsa Jina Amini’s killing, her father confronted her about her headscarf. When Sara admitted she no longer wore it, he told her, “If you refuse to respect the law, leave—and only come back when you accept our rules.”

Now Sara lives with her grandmother, a devout Muslim who has come to accept her granddaughter’s choices. “My grandmother used to make a pilgrimage to Karbala every year,” Sara says, referring to the sacred Shia site in Iraq. “But now she tells me, ‘Faith is personal; no one should impose it.’ She blames the regime for brainwashing my father.”

While the Islamic Republic has traditionally weaponized conservative family structures, especially male guardians, as instruments of domestic enforcement, many testimonies show that women are challenging and fracturing familial control, with potential parallel cracks in the state’s broader hold on society.

In Qom, Iran’s religious heartland, Homa, 23, openly defies compulsory hijab despite her father being a cleric. “My father is unhappy, but I still sit in cafés without my headscarf,” she says. She also criticizes foreign and Persian-language media, including Iran International and BBC Persian, for often reinforcing false divisions. “They imply all hijab-wearing women oppose us. Many now openly reject mandatory hijab and have defended us against harassment from morality police.”

In conservative towns, resistance is harder for women, but the investigation shows that many women persist. Setareh, 18, from Dezful—a conservative city in Khuzestan province—says, “Men here have the final say. Many women are scared to challenge it, but after Mahsa and Armita’s deaths, things began shifting slowly.”

The death of Armita Geravand in 2023—a teenager who fell into a coma and later died after a widely reported altercation with the state’s so-called morality police over her refusal to wear the hijab—became a turning point for many women like Setareh.

Setareh recalls how her own father once slapped her after neighbors accused her of being a “bad influence” on local youth. She later confronted him at a café: “I asked, ‘Am I naked?’ He said no, but worried about what people might think. I told him, ‘Dad, I’m your daughter, not theirs.’” Though he still struggles with her choices, he has gradually distanced himself from the conservative neighbors who once shaped his views.

This generational shift resonates with Mahdieh, 37, a mother who gives her teenage daughters freedom regarding hijab despite opposition from her husband’s family. Mahdieh, who wears hijab by choice, says her husband initially resisted her approach but changed after witnessing state violence firsthand. Their car has been seized three times due to her daughters’ refusal to wear hijab inside. “But my daughters tell me, ‘We are standing strong,’” Mahdieh says.

Fracturing of state’s societal division

In its bid to maintain control, the Iranian state has long sought to divide society by leveraging symbols of loyalty—veiled, chador-wearing women and families of Iran-Iraq War martyrs—against those who reject compulsory hijab. Since the 1980–1988 war, the state has elevated martyrs’ families as guardians of revolutionary ideals, using their sacrifice to enforce loyalty and religious codes across society.

Even today, videos circulate showing clerics confronting unveiled women on the streets, invoking the “blood of martyrs” and insisting that covering oneself is a duty owed to the Islamic Revolution’s sacrifices.

Dozens of interviews for this investigation, however, reveal that in the wake of the 2022–23 Women, Life, Freedom movement, this once-effective strategy of division is beginning to fracture.

Gohar, from a rural village, spent a year challenging her family's resistance to her removing her hijab. Her mother, formerly a staunch state supporter, began questioning religious justifications after Armita Geravand’s killing. “My mother confronted my father, asking, ‘Where in the Quran does it say to kill girls over hair?’” says Gohar. “She now walks fully covered beside me, even as I go unveiled.”

Similarly, older religious women increasingly reject state narratives. Moloud, 70, stopped wearing hijab after the 2022 protests. Whenever morality police approach, she cites Surah An-Nisa, which exempts older women from veiling requirements.

Her religiously grounded defiance highlights weakening loyalty among previously compliant groups.

Somiyah, who spent five years behind bars after the 1979 revolution, recalls the brutal hijab crackdowns of the 1980s in Kerman—when she says unveiled women were thrown into wells. “No one spoke out,” she says.

Women interviewed for this investigation say this surge of defiance isn’t confined to Kerman’s streets—it ripples through everyday acts of grassroots protest across Iran.

On Qeshm Island—located in the Persian Gulf off Iran’s southern coast—Melody’s women-only guesthouse was repeatedly shut down after guests posted unveiled photos online. Melody, 25, says she challenged each closure by appealing to local authorities with “logic, evidence, and religious arguments,” and believes this approach has gradually influenced community attitudes.

Raha, a journalist, was arrested during the 2022 protests and subsequently barred from using social media. Undeterred by Tehran’s heavy-handed internet censorship, she now posts on a relative’s account to challenge the state.

“The reality of Iranian society is that as you walk down any street in any city, you will see many unveiled women dressed beautifully—wearing jeans, loose T-shirts, colorful skirts and jackets, bright earrings, with long or short dyed hair.

omen continue their fight wherever and however they can,” Raha says.

When asked about the spirited debates among opposition circles abroad, she dismisses them as “petty arguments” that, in her view, “have little relevance to the everyday reality of Iran, where women are fighting every day for the right to wear what they choose.”

From civil resistance to active confrontation

While many women remain committed to peaceful civil resistance, others told Iran International that over four decades of peaceful protest against the state have yielded minimal results and that direct confrontation is now necessary.

Manzar, 30, believes in actively confronting security forces. She criticizes those who remain passive or only film brutality. Arrests occur in stages, she explains: first, uniformed police and female dress-code enforcers, then plainclothes agents swiftly preventing intervention.

Shokoofeh, 33, shares a confrontational approach. “If they warn me quietly, I shout back: ‘My body belongs to me, not the regime,’” she says.

Elaheh insists civility with dress-code enforcers is ineffective. “We must be willing to pay the price for freedom,” she argues. “They must get used to our defiance.”

Rising punishments, rising resilience

Since September 2022, the Iranian state has dramatically escalated penalties for hijab defiance—imposing crippling fines, seizing vehicles, revoking housing or campus accommodation, and expelling women from universities.

Dozens of women, however, told Iran International that the penalties and measures have not halted their determination.

Zahra, a PhD student expelled for taking part in protests, describes how solidarity has only grown: “Every hour, we resist. Are we afraid? Of course. But we draw strength from each other.” She notes that ordinary bystanders—once hostile or indifferent—now offer clandestine support, as the state’s harsh crackdowns on dissent continue.

Maryam says her own path was irrevocably changed when she witnessed the killing of Ghazaleh Chalabi—a young protester whose final moments were recorded on her phone as she urged others, “Don’t be afraid,” before she was shot.

“That night, I decided I’d never wear the regime’s ‘rag’ again,” Maryam says. She criticizes how both domestic and foreign media focus on arrests as though they represent defeat. “They present our struggle as if arrests mean we have lost. But they never show how we fight for our freedom every single day.”

Almost all of the women interviewed say the fight against the compulsory hijab is part of the country’s broader struggle for basic human rights and freedom.

Seventeen-year-old Hoveyda, arrested during the 2022 protests, refuses to hide her defiance.

Removing my headscarf for the first time, feeling the wind on my hair—that freedom is indescribable. You have to be a woman in Iran to understand,” she says, explaining that every moment of visibility is a deliberate act of resistance