No love lost:

The six men who forged Iran and the Taliban’s unlikely bond

The rise, fall and rise anew of Taliban commanders who ricocheted back and forth between Iran and Afghanistan amid decades of war tells the story of a bond strengthened in the shadows.

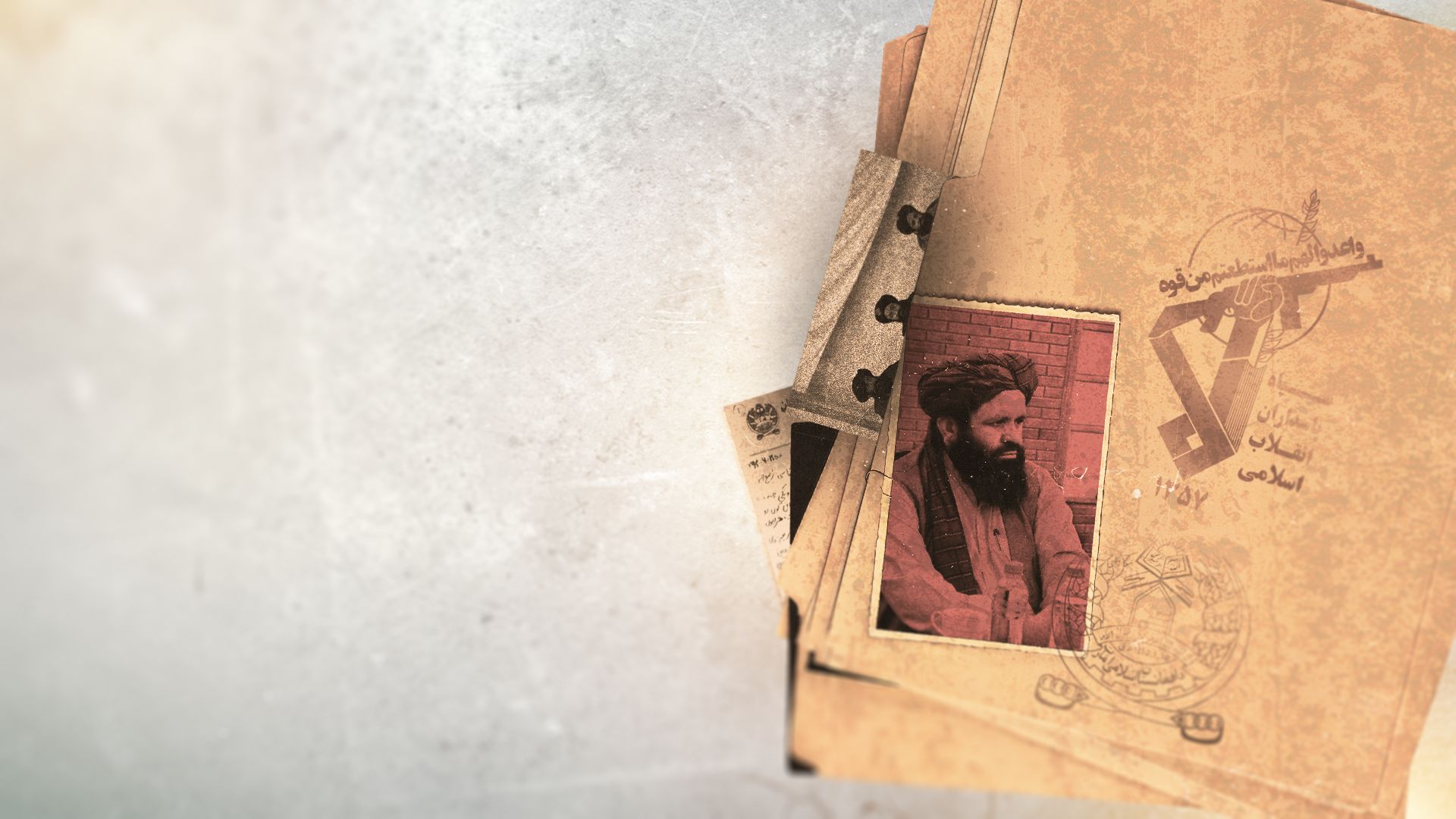

A relentless Taliban insurgency which ultimately ousted the Americans presented an opportunity for the Iranian spies who for two decades cultivated ties with the likes of Mullah Shirin Akhund.

Mullah Shirin, a guerrilla boss who once commanded thousands of gunmen in the retinue of the group’s leader-caliph Mullah Omar, fled the US-led invasion of his homeland to Iran and took up fuel smuggling in frontier badlands with Tehran’s blessing. Iran’s patient patronage has won a trusted advocate now that Shirin is once again a top Taliban decision-maker.

Iran’s Revolutionary Guards built up contacts and backers among senior Taliban leaders who shuttled between the two countries, according to an Afghanistan International investigation, cementing a loveless alliance of calculated interest.

The Islamic Republic of Iran and Taliban-run Afghanistan - two pariah powers squeezed by the United States and weary from confronting it – have made unlikely common cause.

One is a Shi’ite theocracy, the other a Sunni caliphate. Outwardly, they have bitterly detested each other for decades, but both hate Washington and Islamic State more.

They now drift closer in an explosive neighborhood, linked together by a heavily armed cast of guerrilla leaders, jihadi mullahs, drug-runners, insurgents and spies, the investigation found.

Interviews with over a dozen current and former Taliban officials as well as ex-Afghan government intelligence agents, ambassadors and security chiefs illuminate the secret relationship.

Some Senior Taliban commanders, they said, now even receive monthly cash payments, visas, and travel documents for relatives and smuggle drugs and black market cash to Iran.

For Iran, bleeding its top adversary the United States in a grueling war next door was an opportunity not to be missed.

But Tehran now needs friends more than ever as its strength across the Middle East has been sapped by a punishing 14-month war with Israel, especially in Syria.

Afghanistan provides strategic depth and a partner in crushing Islamic State and another fearsome Sunni jihadist group, Jaish al-Adl.

For the Taliban, the only rulers of a country on earth not to be officially recognized by any other state, staying on Iran’s good side ensures a stable backyard as it struggles under sanctions and is in open combat with Pakistan - once its top patron.

Tehran’s initiative to nurture personal contacts with top Taliban leaders has won it a faction sympathetic to its interests in Kandahar, the group’s stronghold.

With enemies and problems multiplying, now at least they have each other.

From hatred to accommodation

At the beginning of the Taliban's first period of rule over parts of Afghanistan from 1996 to 2001, relations were strained, with Pakistan's influence over the Taliban significantly stronger than that of Iran or any other country.

An attack on the Iranian consulate of Mazar-e-Sharif in 1998 as the Taliban was besieging the city amid an Afghan civil war killed 11 Iranian diplomats and staffers, souring ties early.

Taliban Afghanistan’s hosting of al-Qaeda and its training camps made it an enemy to regional neighbors and the world, but Tehran early on viewed the Taliban as an important buffer between it and the international militant organization.

Some members of the Taliban movement became valuable assets for Tehran when their relationship began in the 1990s, largely driven by strategic and regional interests.

After the fall of Taliban rule in 2001 and during the US occupation of Afghanistan, Tehran viewed the Taliban as a tool to wreak military and economic damage on the United States.

This goal aligned with the Taliban's, and the convergence of interests convinced Tehran to indirectly support the Taliban by providing resources and safe havens, sustaining a low-intensity conflict that weakened and ultimately demolished the Western-backed Afghan government.

The Taliban insurgency against US-led forces served Iran’s interests by keeping Afghanistan unstable enough to prevent it from becoming either a hub for anti-Iran forces or a long-term US military hub on its doorstep.

With Washington ejected from Kabul and Tehran suffering ever more setbacks following the October 7 region-wide melee with Israel, the relationship appears set to bloom further.

Cooperation is expanding in border security, trade and regional counterterrorism efforts, with the personal ties cultivated with top Taliban commanders safeguarding Iran's interests in an ever more troubled neighborhood

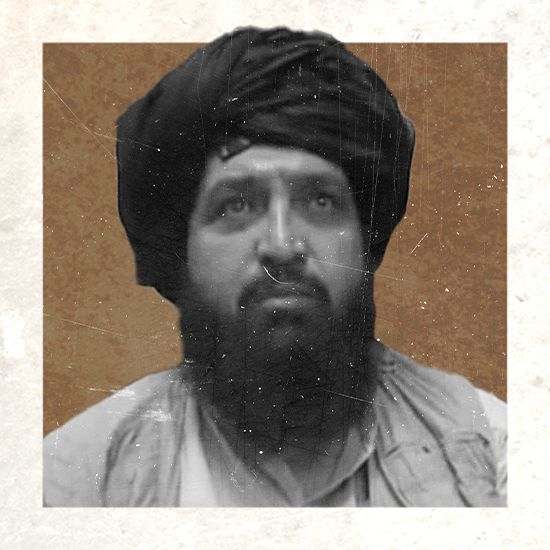

Mohammad Ibrahim Sadr

A faithful friend of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards

A main conduit of Iran's influence via its Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps is the head of the Taliban’s security council, Mullah Mohammad Ibrahim Sadr, according to diplomatic and intelligence officials interviewed by Afghanistan International.

The veteran commander who hails from southwestern Helmand province served as a deputy defense minister during the Taliban’s reign in the 1990s before slipping into Iran in the wake of the 2001 US-led invasion and slowly becoming a trusted ally of Tehran.

"Iran views Sadr as a strategic partner, especially given his role in the Taliban as the head of military operations and the Security Council," said a source familiar with Iran's security operations.

Taking refuge in the Eastern Iranian cities of Mashhad, Zahedan and Khosf in South Khorasan province, Ibrahim Sadr established the al-Omaria madrassa, or religious seminary, in the town of Nosratabad in neighboring Sistan-Baluchistan province in 2008.

The madrassa provided training to Taliban fighters from across Afgahnistan, from Helmand in the West to Ghazni, Zabul and Kandahar in the far East fighting the US-led coalition in Helmand, according to a religious teacher familiar with its operations and a former Afghan diplomat.

"The madrassa was a clandestine operational intelligence center which Iran provided with financial and logistical support," a former intelligence official told Afghanistan International on condition of anonymity. "Its goal was to increase its presence on the common borders of Afghanistan and Iran and prevent the spread of American influence in Iran."

A mysterious explosion hit the madrassa in 2017 killed 11 Taliban fighters. Security sources told Afghanistan International that intelligence agents from the now-toppled Afghan government carried out the attack but kept their role silent so as not to arouse Iranian ire.

The mutual embrace of Ibrahim Sadr and Iran soon came to Washington’s attention.

“In 2018, Iranian officials agreed to provide Ibrahim with monetary support and individualized training in order to prevent a possible tracing back to Iran,” the US Treasury said in an October announcement designating Ibrahim Sadr a conduit for Tehran’s funding of the Taliban.

“Iranian trainers would help build Taliban tactical and combat capabilities,” it added.

After the US sanctions designation and the explosion at Ibrahim Sadr’s seminary, former Afghan government security officials say Iran’s IRGC agreed to provide him more financial support and weapons provided he keep links to Tehran invisible.

Under this policy, Iranian aid regularly arrived at Ibrahim Sadr’s new Iranian madrassa and others he ran in Pakistan’s North West Frontier Province, according to two top former Afghan security officials and a former diplomat.

In Iran, IRGC trainers worked to enhance the Taliban's combat capabilities.

"The Taliban received Iranian weapons during these years, including rifles,” a former official of the previous government’s National Directorate of Security (NDS), the main intelligence body, told Afghanistan International.

From 2016 to 2020, Ibrahim Sadr was the head of the Taliban's military commission based in Peshawar in neighboring Pakistan - a position that gave him leadership of the battles in Helmand province, where he fought fierce and bloody battles against coalition-backed Afghan forces.

Iranian support supercharged a broad restructuring Ibrahim Sadr made of Taliban forces, according to top former Afghan government security officials and a Taliban source, contributing significantly to the Taliban's military victory in Helmand.

"Ibrahim Sadr is not just a commander but he is an important pillar of the Taliban's military restructuring," a source close to the Taliban said.

Ibrahim Sadr’s personal life is also intertwined with his political and military activities. Both his wives lived in Iran until 2020.

Cross-border drug smuggling between Helmand and Iran via Pakistan fueled the Taliban’s money-making operations under Ibrahim Sadr with Iranian blessing, a former senior Taliban official and two top security officials with the ousted government said.

The Afghan government believed its forces had killed Ibrahim Sadr in battle in 2020 but were vexed that he had survived and had convalesced in an Iranian hospital.

Ibrahim Sadr has expanded his influence from Helmand to the Taliban's decision-making nerve center of Kandahar, elevating its relationship with Iran to a new level.

Under the current Taliban leadership, Ibrahim Sadr's role remains central to the group's diplomatic and military strategy.

A main conduit of Iran's influence via its Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps is the head of the Taliban’s security council, Mullah Mohammad Ibrahim Sadr, according to diplomatic and intelligence officials interviewed by Afghanistan International.

The veteran commander who hails from southwestern Helmand province served as a deputy defense minister during the Taliban’s reign in the 1990s before slipping into Iran in the wake of the 2001 US-led invasion and slowly becoming a trusted ally of Tehran.

"Iran views Sadr as a strategic partner, especially given his role in the Taliban as the head of military operations and the Security Council," said a source familiar with Iran's security operations.

Taking refuge in the Eastern Iranian cities of Mashhad, Zahedan and Khosf in South Khorasan province, Ibrahim Sadr established the al-Omaria madrassa, or religious seminary, in the town of Nosratabad in neighboring Sistan-Baluchistan province in 2008.

The madrassa provided training to Taliban fighters from across Afgahnistan, from Helmand in the West to Ghazni, Zabul and Kandahar in the far East fighting the US-led coalition in Helmand, according to a religious teacher familiar with its operations and a former Afghan diplomat.

"The madrassa was a clandestine operational intelligence center which Iran provided with financial and logistical support," a former intelligence official told Afghanistan International on condition of anonymity. "Its goal was to increase its presence on the common borders of Afghanistan and Iran and prevent the spread of American influence in Iran."

A mysterious explosion hit the madrassa in 2017 killed 11 Taliban fighters. Security sources told Afghanistan International that intelligence agents from the now-toppled Afghan government carried out the attack but kept their role silent so as not to arouse Iranian ire.

The mutual embrace of Ibrahim Sadr and Iran soon came to Washington’s attention.

“In 2018, Iranian officials agreed to provide Ibrahim with monetary support and individualized training in order to prevent a possible tracing back to Iran,” the US Treasury said in an October announcement designating Ibrahim Sadr a conduit for Tehran’s funding of the Taliban.

“Iranian trainers would help build Taliban tactical and combat capabilities,” it added.

After the US sanctions designation and the explosion at Ibrahim Sadr’s seminary, former Afghan government security officials say Iran’s IRGC agreed to provide him more financial support and weapons provided he keep links to Tehran invisible.

Under this policy, Iranian aid regularly arrived at Ibrahim Sadr’s new Iranian madrassa and others he ran in Pakistan’s North West Frontier Province, according to two top former Afghan security officials and a former diplomat.

In Iran, IRGC trainers worked to enhance the Taliban's combat capabilities.

"The Taliban received Iranian weapons during these years, including rifles,” a former official of the previous government’s National Directorate of Security (NDS), the main intelligence body, told Afghanistan International.

From 2016 to 2020, Ibrahim Sadr was the head of the Taliban's military commission based in Peshawar in neighboring Pakistan - a position that gave him leadership of the battles in Helmand province, where he fought fierce and bloody battles against coalition-backed Afghan forces.

Iranian support supercharged a broad restructuring Ibrahim Sadr made of Taliban forces, according to top former Afghan government security officials and a Taliban source, contributing significantly to the Taliban's military victory in Helmand.

"Ibrahim Sadr is not just a commander but he is an important pillar of the Taliban's military restructuring," a source close to the Taliban said.

Ibrahim Sadr’s personal life is also intertwined with his political and military activities. Both his wives lived in Iran until 2020.

Cross-border drug smuggling between Helmand and Iran via Pakistan fueled the Taliban’s money-making operations under Ibrahim Sadr with Iranian blessing, a former senior Taliban official and two top security officials with the ousted government said.

The Afghan government believed its forces had killed Ibrahim Sadr in battle in 2020 but were vexed that he had survived and had convalesced in an Iranian hospital.

Ibrahim Sadr has expanded his influence from Helmand to the Taliban's decision-making nerve center of Kandahar, elevating its relationship with Iran to a new level.

Under the current Taliban leadership, Ibrahim Sadr's role remains central to the group's diplomatic and military strategy.

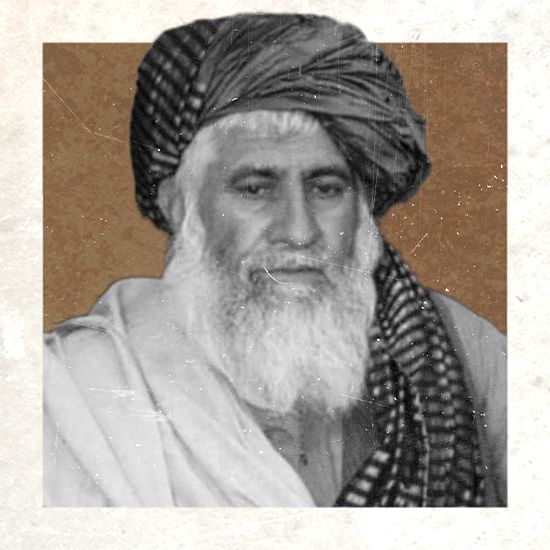

Abdul Haq Wasiq

Iran’s link to the Taliban spy agency

When the Taliban rose from relatively obscurity to take control of three-quarters of Afghanistan in 1996 and straddle Iran's borders, the group’s hardline Sunni jihadist stance and the presence of veteran anti-Shia Pakistani fighters in its ranks jarred Tehran.

But a Taliban luminary who once lived in Iran and whose career spanned the notorious US prison camp in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba to heading the Taliban spy agency has deftly salved ties.

Abdul Haq Wasiq lived with his family in Zahedan in eastern Iran before the formation of the Taliban in the early 1990s and its eventual takeover.

His brother-in-law Qari Ahmadullah headed another Islamist group, Hizb-e-Islami, in Sistan-Baluchistan province in southeastern Iran at the time.

When the Taliban conquered Kabul, Ahmadullah was appointed head of the Taliban's intelligence agency and Wasiq was first his aide then rose to head of Taliban intelligence for Kabul.

His remit later expanded to monitoring other extremist militant groups in Pakistan and Iran.

In 1998, Wasiq shuttled among the domains of four extremist groups who had yet to throw in their lot with the Taliban in meetings that took place in Quetta in neighboring Pakistan, Bahramcha in southwest Helmand province and Sistan-Baluchistan in southeast Iran.

Signing a five-way agreement in Helmand with the groups, Wasiq earned Mullah Omar’s trust and became one of his closest aides tasked with one of the Taliban’s trickiest dossiers: managing the reclusive leader’s diplomacy with Iran.

After his appointment as deputy intelligence chief, two former senior Taliban officials said, he was assigned by then-leader Mullah Omar to manage relations with Iran and European countries.

Wasiq was a key conduit between the Taliban and al-Qaeda, according to US diplomatic cables revealed by Wikileaks. Coalition forces invading Afghanistan apprehended him in November 2001 and transferred him to United States’ Guantanamo Bay prison in Cuba, where Wasiq would remain for 12 years.

Wasiq was alleged to have provided safe havens for several al-Qaeda members on the border with Iran, transporting and equipping pro-Iranian al-Qaeda factions to Ghazni, Paktika and the site of its last stand at Tora Bora and overseeing security at the group’s training camps.

His first wife, mother, and family emigrated to Iran in 2002 and settled in a small town in Eastern Zahedan province, according to a former Taliban official, cementing personal ties with Tehran.

Three members of his family joined Sadr Ibrahim at the al-Omaria Madrassa in southeast Iran, and another brother-in-law was killed in the explosion at the seminary in 2017.

Released by the United States in a Qatari-brokered prisoner exchange for US soldier Bowe Bergdahl, Wasiq was transferred to Qatar in 2014, where he served as a key member of the Taliban’s negotiating team in Doha.

Wasiq first travelled from Qatar to Islamabad, then to Balochistan, and finally to Iran in October 2016 to rejoin his family, a former diplomat and senior government official said.

“We were aware of his trip in 2016 and shared this concern with Iran and Pakistan at the diplomatic level after reporting it to the Joint Intelligence Command,” a former deputy director of operations for Afghanistan’s National Directorate of Security told Afghanistan International.

Wasiq, he added, travelled to Iran four times between 2014 and 2021, rebuilding ties with the IRGC which had faded during his long imprisonment.

In October 2022, Wasiq met with Deputy Central Intelligence Agency Director David Cohen in Doha, marking the first time that the two sides had met at such a senior level since the US assassination of al-Qaeda leader Al-Zawahiri in Kabul earlier that year.

Neither the US nor the Taliban government has described the contents of the meeting.

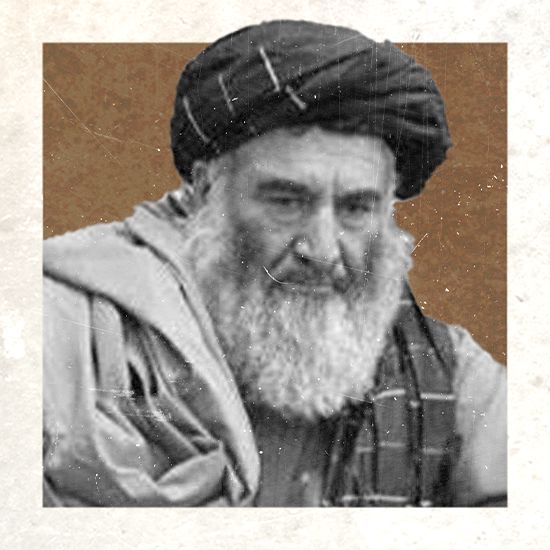

Abdul Qayyum Zakir

Al-Qaeda and Iran’s middleman

A high-stakes prisoner exchange between arch-foes al-Qaeda and Iran was managed by a maverick Taliban leader whose proximity to the jihadists Tehran detested, but whose usefulness in handling them Iran came to value.

In 2010, the IRGC agents handed over Saif al-Adel, a senior member of al-Qaeda who now leads the network after al-Zawahiri's death to Taliban-aligned militants in exchange for an Iranian diplomat abducted in Pakistan, Heshmatollah Attarzadeh-Nyaki.

Senior Taliban commander Abdul Qayyum Zakir played a main role in the delicate talks.

Zawahiri bought 150 cars for Zakir in his battles with the Taliban’s foes in the 1990s, providing key support to battlefield advances. Known for his personal charisma and military know-how, Zakir would play a key role in the Taliban's resurgence.

Zakir commanded Taliban forces in some of its fiercest combat, in northern Afghanistan during the group’s reign in the 1990s and is considered one of the group’s most hardened commanders.

His path took him to dismal lows and spectacular highs.

Captured in a fierce battle in 2001 by forces led by ruthless anti-Taliban warlord Abdul Rashid Dostum, he was turned over to American forces who locked him away at Guantanamo Bay.

But in a tortuous path leading through Pakistan and Iran, he ultimately stormed the Afghan presidential palace at the head of victorious Taliban forces retaking the capital Kabul on 15 August 2021 and sat in the chair of the former president Ashraf Ghani, who had fled.

Amid his early ordeals, his family in 2003 moved to Zahedan in Eastern Iran where his three wives lived with their children, his brother and six brothers-in-law.

Transferred to Pul-e-Charkhi prison in Kabul in 2007, Zakir was released again in 2008 out of hope that his release and that of other Taliban leaders could galvanize a peace process.

But upon his release, Zakir re-joined the Taliban’s military leadership, moving from Helmand in southwest Afghanistan to Quetta in Pakistan and ultimately to Zahedan.

Nearby he established a religious school in the Ashar area of Sistan-Baluchistan called Khalid bin Waleed, which provided combat training to Taliban recruits from Helmand, Zabul, Nimroz, and Farah provinces in addition to providing religious education.

"The madrassa was established with the direct cooperation of the government of the Islamic Republic of Iran,” a former head of the National Directorate of Security (NDS) of the former government of Afghanistan told Afghanistan International.

Now he is the Taliban's deputy defense minister and chief of Taliban leader Mullah Haibatullah's security council in Kandahar.

Mohammad Barich

The drug-trafficking kingpin

One of the key currencies of a dicey Tehran-Taliban relationship where ideologies clashed was more universal: drugs.

From a money-changer on a Pakistani street to a US-designated global drug lord, Mohammad Naeem Barich put himself at the center of this cross-border trade.

In identifying him as a so-called Foreign Narcotics Kingpin, the US Treasury in 2012 said Barich was “managing the Taliban’s relationship with Iran.”

Outwardly anathema to both Islamist systems, overseeing the shipment of opiates grown in Afghanistan and shipped abroad via Iran was key to gaining foreign exchange barred by sanctions and managing unruly, heavily armed criminal underworlds.

Deputy minister of tribal affairs during the Taliban's rule in the 1990s and later deputy minister of civil aviation, Barich drifted over the border to Quetta in Pakistan after the Taliban’s fall in 2001.

His money exchange shop there was raided by Pakistani police in 2002 and Barich was briefly arrested for money-laundering on the Taliban’s behalf, after which he travelled to Iran with his wife, according to a former Taliban official.

Shortly afterwards, he returned to Kandahar and joined the Taliban's military commission.

Barich ultimately became the group’s shadow governor for Helmand province and smuggled coveted dollars at the regional level, conveying some of the black market cash from Afghanistan's southern provinces to Iran.

Signaling his graduation into the narcotics trade, a heroin processing factory in the Bahramacha district of Helmand owned by Barich was bombed in 2009, according to former Afghan government officials, killing his cousin.

Barich used a UN-sanctioned money exchange company called the Rahat Trading Company with branches in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran to launder money from the trade, according the US Treasury.

Mawlawi Noor Ahmad Islamjar

The Iranian Mullah

Not a militant but a cleric provided Iran with some of its most useful ammunition against a persistent menace to the Islamic Republic’s side, the Jaish al-Adl militant group.

The Sunni jihadist group hailing mostly from the Baluch ethnic group in southwest Iran has launched years of deadly attacks against Iran’s Revolutionary Guards and other security organs.

A fatwa or religious decree issued by Taliban-aligned Afghan cleric Mawlawi Noor Ahmad Islamjar in 2018 calling Jaish al-Adl an infidel group fighting an unjust cause undermined its following.

Islamjar is a puritanical Sunni preacher whose roots in Iran and influential seminary in the Western Afghan city of Herat garnered himself a religious following on both sides of the border.

The jeremiad against the militants, former Afghan security and local officials said, was made at the instigation of Iranian intelligence handlers with whom Islamjar had been in touch since shortly after he fled nextdoor following the US invasion.

His ancestors migrated to Herat from the Piranj region of the Khorasan Razavi province in northeast Iran, assimilated with Afghan society and his father was also a hardline cleric.

A junior judge in Western Afghanistan during the first Taliban reign in the 1990s, upon their ouster he moved to the obscure town of Kohabad in Iran’s northeast Khorasan Razavi province, where Islamjar opened a shop and established a madrassa in 2004.

Returning to Herat in 2007, Islamjar established another madrassa there which was raided by Afghan intelligence officials who detained him on charges of running the school with Iranian funds and teaching extremism, security officials from the toppled government said.

In time he acquired the sobriquet among locals of “the Iranian mullah”. While staying out of formal politics, Islamjar is considered a confidant of Ibrahim Sadr and Qayyum Zakir, whom former Afghan government officials say he befriended while all were in Iran.

Not a militant but a cleric provided Iran with some of its most useful ammunition against a persistent menace to the Islamic Republic’s side, the Jaish al-Adl militant group.

The Sunni jihadist group hailing mostly from the Baluch ethnic group in southwest Iran has launched years of deadly attacks against Iran’s Revolutionary Guards and other security organs.

A fatwa or religious decree issued by Taliban-aligned Afghan cleric Mawlawi Noor Ahmad Islamjar in 2018 calling Jaish al-Adl an infidel group fighting an unjust cause undermined its following.

Islamjar is a puritanical Sunni preacher whose roots in Iran and influential seminary in the Western Afghan city of Herat garnered himself a religious following on both sides of the border.

The jeremiad against the militants, former Afghan security and local officials said, was made at the instigation of Iranian intelligence handlers with whom Islamjar had been in touch since shortly after he fled nextdoor following the US invasion.

His ancestors migrated to Herat from the Piranj region of the Khorasan Razavi province in northeast Iran, assimilated with Afghan society and his father was also a hardline cleric.

A junior judge in Western Afghanistan during the first Taliban reign in the 1990s, upon their ouster he moved to the obscure town of Kohabad in Iran’s northeast Khorasan Razavi province, where Islamjar opened a shop and established a madrassa in 2004.

Returning to Herat in 2007, Islamjar established another madrassa there which was raided by Afghan intelligence officials who detained him on charges of running the school with Iranian funds and teaching extremism, security officials from the toppled government said.

In time he acquired the sobriquet among locals of “the Iranian mullah”. While staying out of formal politics, Islamjar is considered a confidant of Ibrahim Sadr and Qayyum Zakir, whom former Afghan government officials say he befriended while all were in Iran.

Mohammad Shirin Akhund

Scourge of Jaish al-Adl

Mullah Mohammad Shirin Akhund rose to become one of the Taliban’s top guerrilla leaders and diplomats, but earned his stripes in a grubby cross-border fuel smuggling trade where his deadly shoot-outs with Jaish al-Adl militants earned him Tehran’s favor.

Over the years, he would become a key Iranian asset in sapping their strength and denying them a haven in Afghanistan.

“(Shirin is) being financed by Iran to kill members of the Jaish al-Adl group in Afghanistan, extradite them to Iran, or share information about them with Iranian authorities,” a source with knowledge of the matter in his native Kandahar told Afghanistan International.

“All senior and low-ranking members of Jaish al-Adl and other anti-Iranian groups are registered with the Taliban's provincial intelligence departments," the source added.

A close friend and colleague of late Taliban founder Mullah Mohammad Omar, Shirin was responsible for the late leader’s security and commanded the some 2,700-strong force tasked with his security.

After the fall of the Taliban, he moved first to the town of Chaman just across the border from his native Kandahar in Pakistan, then to Zahedan in Iran where he started a fuel smuggling business into Pakistan and Afghanistan, according to a top former Afghan security official and Taliban sources.

Crisscrossing smuggling routes in the Afghan-Pakistan-Iran border area, Shirin fought running gun battles with Jaish al-Adl militants who regarded him as an interloper in their lawless fief.

Shadow governor of the Taliban for Kandahar during its war with the US-led coalition, his vendetta persisted with the group, who sought refuge from Iranian security forces in ungoverned pockets of Afghanistan.

Deadly raids led by Shirin’s fighters, including in Ghazni in the heart of the country, stoked Jaish al-Adl's desire for revenge. A member of the group attacked Shirin in 2010, lightly wounding him and killing one of his bodyguards.

High-profile military operations cemented Shirin’s role in the top leadership, and he masterminded an attack on the Kandahar governor's office in 2018 that seriously wounded him and killed six diplomats from the United Arab Emirates.

His military prowess won him diplomatic clout as well, and Shirin was sent as a member of the Taliban's delegation to Doha, Qatar for talks with the United States culminating in its withdrawal.

Shirin, now governor of Kandahar and deputy intelligence minister of the Taliban's ministry of defence, is the closest senior official to Taliban leader Mullah Haibatullah Akhundzada, a former Taliban official now estranged from the group told Afghanistan International.

"The Taliban leader has a number of other close pro-Iranian associates who are responsible for the security of the southern region," a former Taliban commander in Kandahar said.

"These individuals are mostly important members of Mullah Haibatullah's circle and trusted people who have a favourable view of Iran.”