The Iranian dissidents forced into exile, who found no refuge in the West

Despite Western leaders' vocal support for dissidents during Iran’s 2022 protests, those who escaped the state's crackdown say safety remains out of reach.

More than two years after the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement, these dissidents tell Iran International that they remain trapped in uncertainty, navigating asylum rejections and bureaucratic delays.

Many, now scattered across Europe, Canada, and Turkey, say they risked everything to escape Iran. While they have eluded imprisonment or worse, these dissidents still face threats and intimidation from Iranian authorities, whose reach extends beyond the country's borders. Some describe receiving anonymous phone calls, online harassment, and warnings—often from individuals with ties to intelligence agencies—urging them to remain silent.

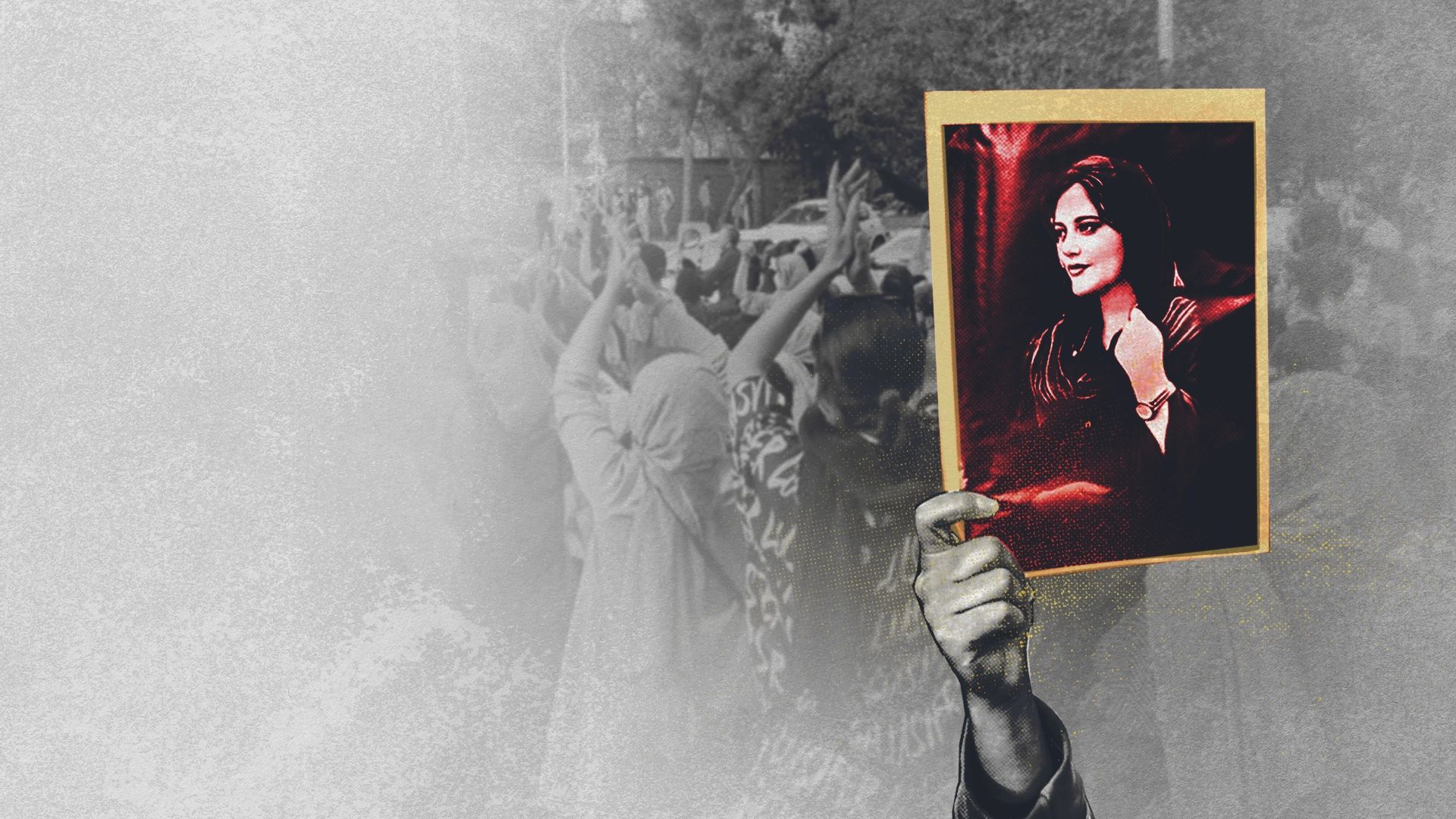

These dissidents’ participation, along with that of thousands of other Iranians, in the nationwide protests against the state captured global attention. Triggered by the in-custody death of 22-year-old Mahsa Jina Amini—for which a UN Fact-Finding Mission later held Iran responsible—the months-long protests became a watershed moment, shaking the foundation of the Islamic Republic.

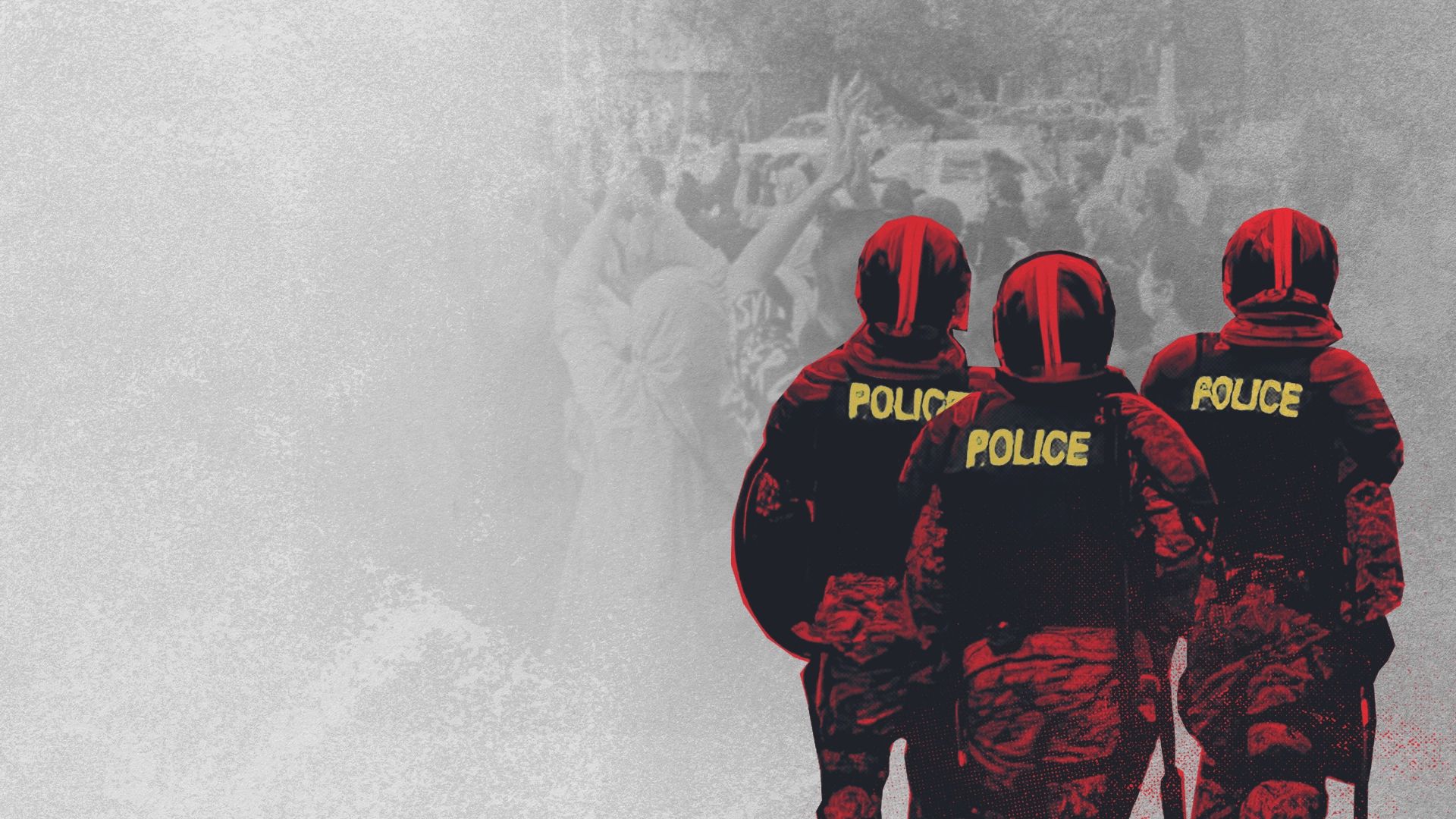

This reckoning was met with a swift and brutal response from Tehran, leading to the arrest of tens of thousands and the deaths of at least 551 individuals, including 68 children. State forces employed extreme measures, including sexual violence, rape, torture, and arbitrary executions to crush the uprising.

Despite the state's crackdown, Iranians continued to call for the Islamic Republic’s downfall, drawing expressions of solidarity from leaders in the United States, Germany, France, and Canada, as well as European officials. Yet dissidents tell Iran International that these declarations have done little to ensure their safety. As they deal with bureaucratic hurdles, prolonged uncertainty, and, in some cases, the threat of deportation, many say they are beginning to question when Western leaders' promises will translate into real protection.

For security reasons, specific details regarding the current circumstances of the interviewed dissidents have been withheld from this report.

The cost of protesting in Iran

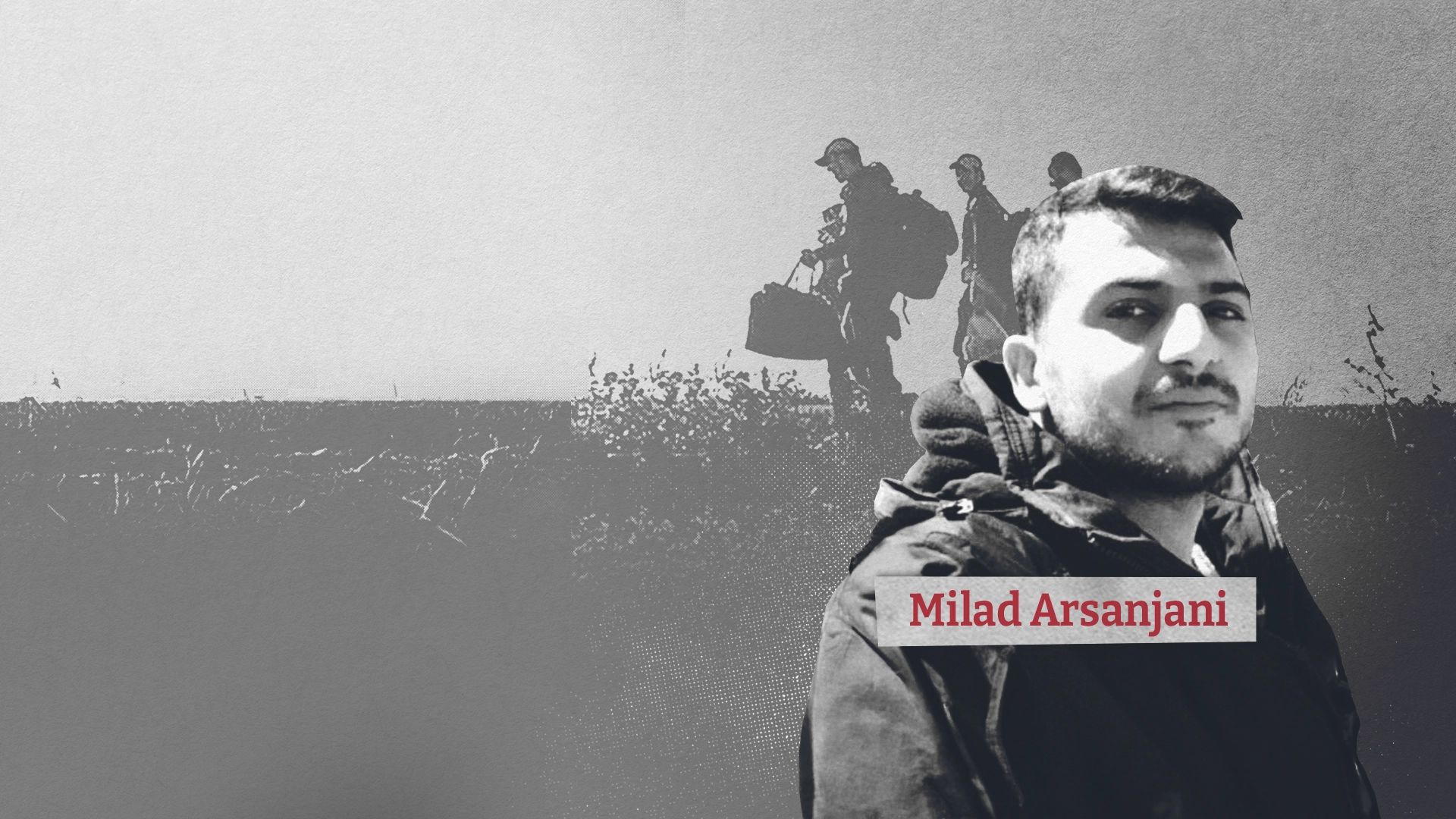

For Milad Arsanjani, fleeing his homeland wasn't a choice—it was, as he puts it, a forced necessity to stay alive. At 30, he first took part in anti-state protests six years ago, and since then, he says he has been targeted by authorities and caught in a cycle of imprisonment.

The nationwide protests in November 2019, known as “Bloody November” among Iranians, saw state forces kill an estimated 1,500 people within two weeks, a number that dissidents and some reports suggest may be significantly higher.

“Since then, the longest period I spent out of prison was two and a half months. Every time I was released, they would arrest me again after a month or two,” Arsanjani says, estimating that he spent about three years in prison in total.

While imprisoned, Arsanjani says he endured both physical and psychological torture, including verbal abuse, brutal beatings, and long stretches in solitary confinement. After serving a six-month sentence for protesting in 2022, he was released but faced repeated death threats from intelligence agents.

After selling everything he had spent his life working for, Arsanjani says he used the money to pay a smuggler and fled Iran, though it was the last thing he wanted. In December 2023, he slipped across the border into Turkey, hoping one day to reach Europe.

A year after seeking asylum in Europe, Arsanjani's journey has been one of constant setbacks. Denied entry into Italy and turned away in Greek waters, he was also expelled from the Malakasa refugee camp near Athens. His asylum claims have been rejected by at least two more European countries since. Yet, he remains hopeful, relentlessly pursuing safety in the West.

Hossein Ashtari was 22 years old, when he says state forces shot him in the face with a paintball gun during the 2022 protests, leaving his left eye with severe damage.

Ashtari is one of more than 580 Iranian dissidents who suffered eye injuries after security forces shot protesters with paintball bullets and pellets, often at close range. He says protesters were deliberately blinded as a means of intimidation. Ashtari claims that authorities, fearful of Western media coverage, have threatened these survivors with arrests and intimidation.

Faced with no option, Ashtari says he fled to Turkey, where he applied for a humanitarian visa to Canada but has yet to receive a response.

Now living in a small Turkish town, and without proper medical care for his eye, he continues to receive threatening calls from Iranian authorities. “They still call from private numbers, threatening me, as if I’m still within their reach,” he says.

Arsanjani, who also continues to face threats, has chosen not to disclose his current location for security reasons.

Reflecting on the challenges of seeking asylum, he contends that the European system prioritizes applicants affiliated with known political groups, leaving independent activists like him at a disadvantage.

“[European immigration officials] keep asking, ‘Which party are you with? What group do you belong to?’” he explains, adding that some refugees suggested he falsely claim religious persecution to improve his chances.

Arsanjani describes himself as a secular activist and says he refused to lie to immigration officials, though many told him his honesty may jeopardize his chances if asylum.

Early this year, Arsanjani's last asylum request was denied.

The persecution of victims’ families

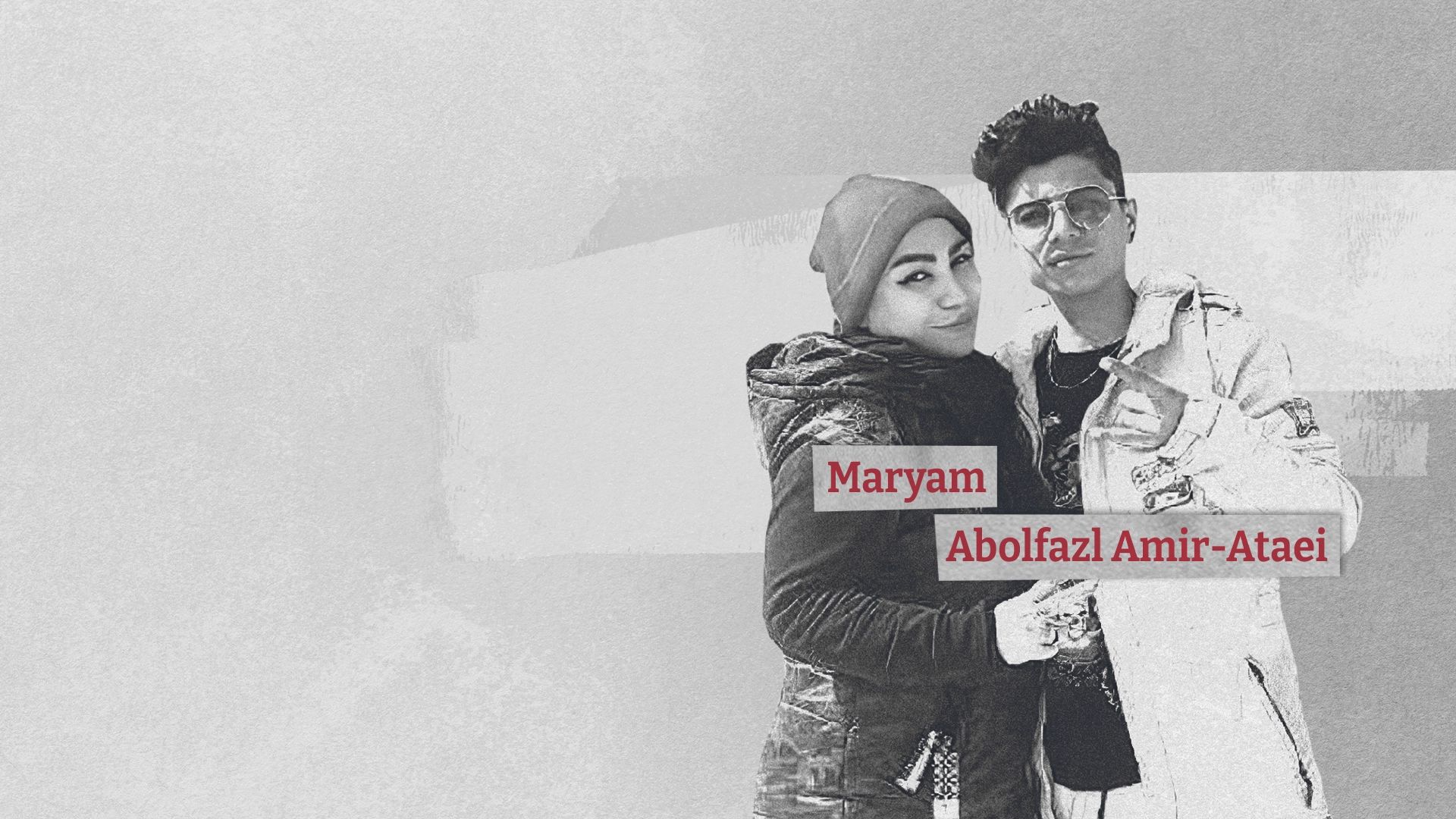

To stifle dissent and prevent future unrest, Iranian authorities often extend their crackdown beyond protesters to include the families of victims and dissidents. Among them is Maryam, the mother of 16-year-old Abolfazl Amir-Ataei, who was fatally shot in 2022 while protesting in Shahr-e Ray, south of Tehran.

Amir-Ataei was struck in the head at close range by a tear gas canister fired by security forces. For the next eight months, Maryam remained by his hospital bedside, holding on to hope for his recovery, even as intelligence agents pressured her to stay silent. Instead of deterring her, she says, their threats only strengthened her resolve to share his story publicly.

“When I saw his body at the morgue, I made him a promise,” she says. “I told him, ‘They won’t silence your voice. You won’t just be buried and forgotten.’”

Even after her son’s death, the threats continued. Maryam says authorities warned her that if she were to suffer a sudden “accident,” they would bear no responsibility. It was then, she says, that she realized staying in Iran would mean risking her own life if she continued to speak out.

With the help of activists in Europe, she fled to Germany, where her asylum claim was approved, granting her a temporary residence permit. In time, her family was able to join her, though Iranian authorities have refused to issue a death certificate or burial permit for her son.

Maryam says that despite it all, she remains committed to keeping her son’s memory alive. “They wanted to erase him,” she said. “But I won’t let them.”

Her story reflects a broader reality for Iranian dissidents in exile—escaping Iran does not always mean escaping danger. While Germany has been a key destination for those fleeing persecution, many Iranian dissidents there remain vulnerable. At the end of 2023, the country allowed its deportation ban to lapse, raising concerns among human rights advocates who warn that returnees face grave risks amid a surge in executions in Iran. They stress the urgent need for continued protections for Iranian asylum seekers.

Still, those who have found refuge are not necessarily safe. Tehran has a long history of targeting dissidents on German soil, using surveillance, intimidation, and assassination plots to silence opposition abroad. Earlier this year, Iran International learned of a plot to assassinate an Iranian dissident singer in Germany, one of several attempts in recent years by Tehran to eliminate critics beyond its borders.

For many Iranians, the danger begins the moment their loved ones are killed. Families seeking justice often find themselves under the same pressure and threats as the dissidents they mourn.

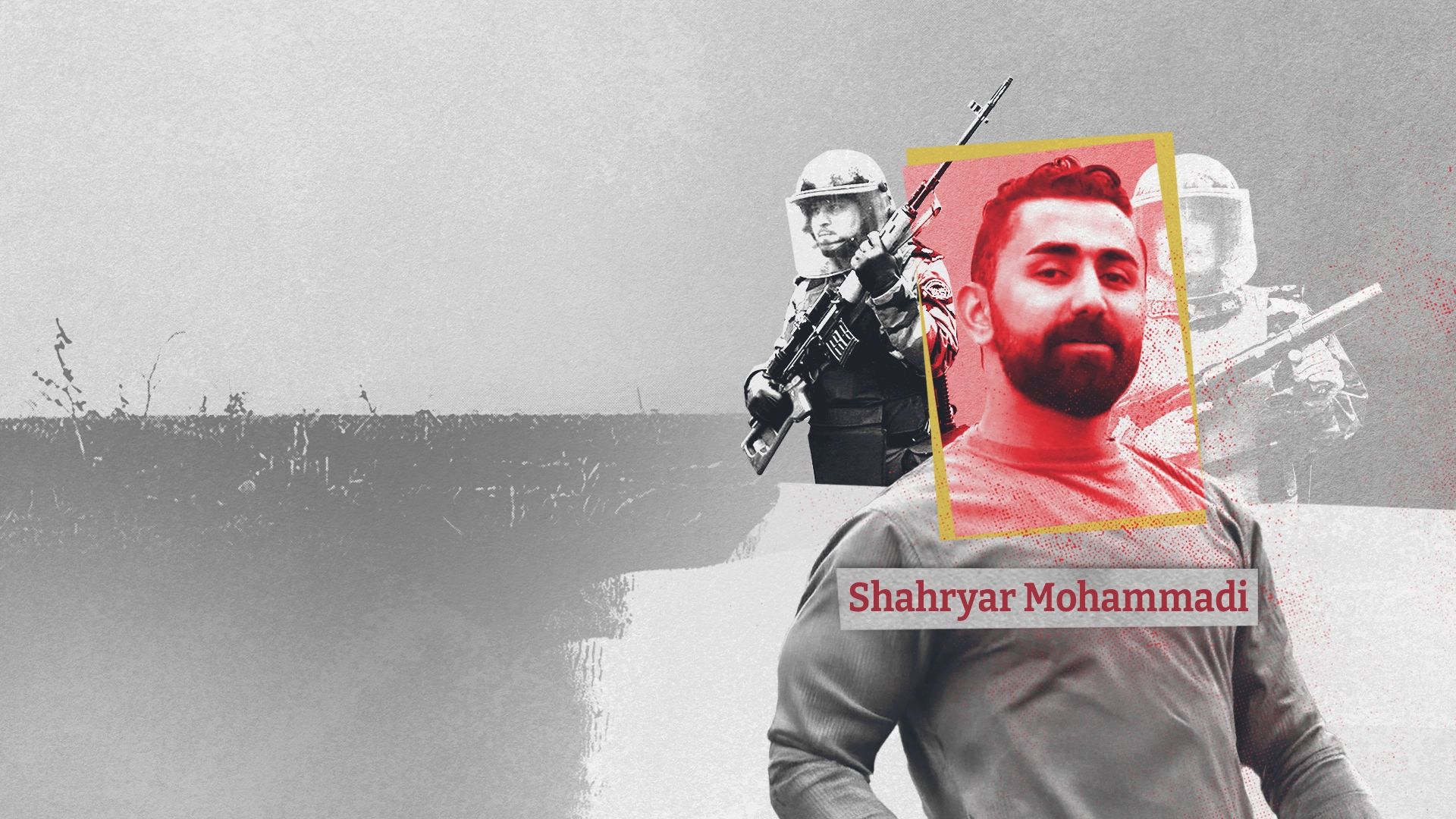

Milad Mohammadi is one of them. He says he became a target of intelligence ministry agents after publicly demanding justice for the murder of his brother, Shahryar Mohammadi.

Shahryar was 28 when he was shot to death by state security forces on November 18, 2022, while driving in Bukan, in Iran's West Azerbaijan province.

That same night, while trying to retrieve his brother’s body from a hospital, Milad says he was ambushed. Security forces opened fire in the hospital's courtyard, shooting him with a Winchester gun — a weapon commonly employed by state authorities.

In the ensuing chaos, both he and his mother were attacked with tear gas and batons, and pellets struck his leg after he collapsed beside his brother’s body. He says officers also fired at his brother’s corpse before injecting him with a sedative in an attempt to force him to relinquish Shahryar’s remains.

Authorities threatened his mother with further repercussions, warning that if they did not comply, the family would never learn where his brother was laid to rest—a tactic of coercion that other dissidents have reported experiencing during the protests.

With the help of friends, he says he was taken to a hospital for treatment before going into hiding. “I never saw Shahryar again or was even able to go to his burial place. Not even once,” Milad said.

After two months in Tehran, he says he felt forced to flee to Iraq, taking a path over the mountains with the assistance of smugglers. Once he arrived, Milad went straight to the UN office to seek asylum, where officials refused to register his claim. When he refused to leave, he said he was arrested and held for 12 days. “I begged them, just give me a reason—why have you arrested me?”

After his release, Milad remained in hiding until he secured a humanitarian visa to Canada.

Several other human rights activists, including high-profile cases, also fled to Iraq before seeking asylum in Canada. Many spent months in hiding there—fearful of Iranian proxies known for targeting dissidents—all while the IRGC continued its missile strikes on Iraqi Kurdistan.

Canada took a vocal stance on the protests—labeling Iran’s government a “brutal regime,” imposing sanctions, and accepting a notable number of Iranian asylum claims. Critics, however, argue that restrictions on humanitarian visas and limited refugee quotas still leave many Iranians stranded in third countries, with few options to reach Canada safely.

In line with other reports from Iranian dissidents, Milad says threats from Islamic Republic supporters have not let up, prompting him to contact Canadian police. Despite ongoing intimidation and the arduous process of getting to Canada, he says he is committed to speaking out, urging the international community “not to turn a blind eye to the crimes of the Islamic Republic and side with the Iranian people.”

Turning pain into advocacy

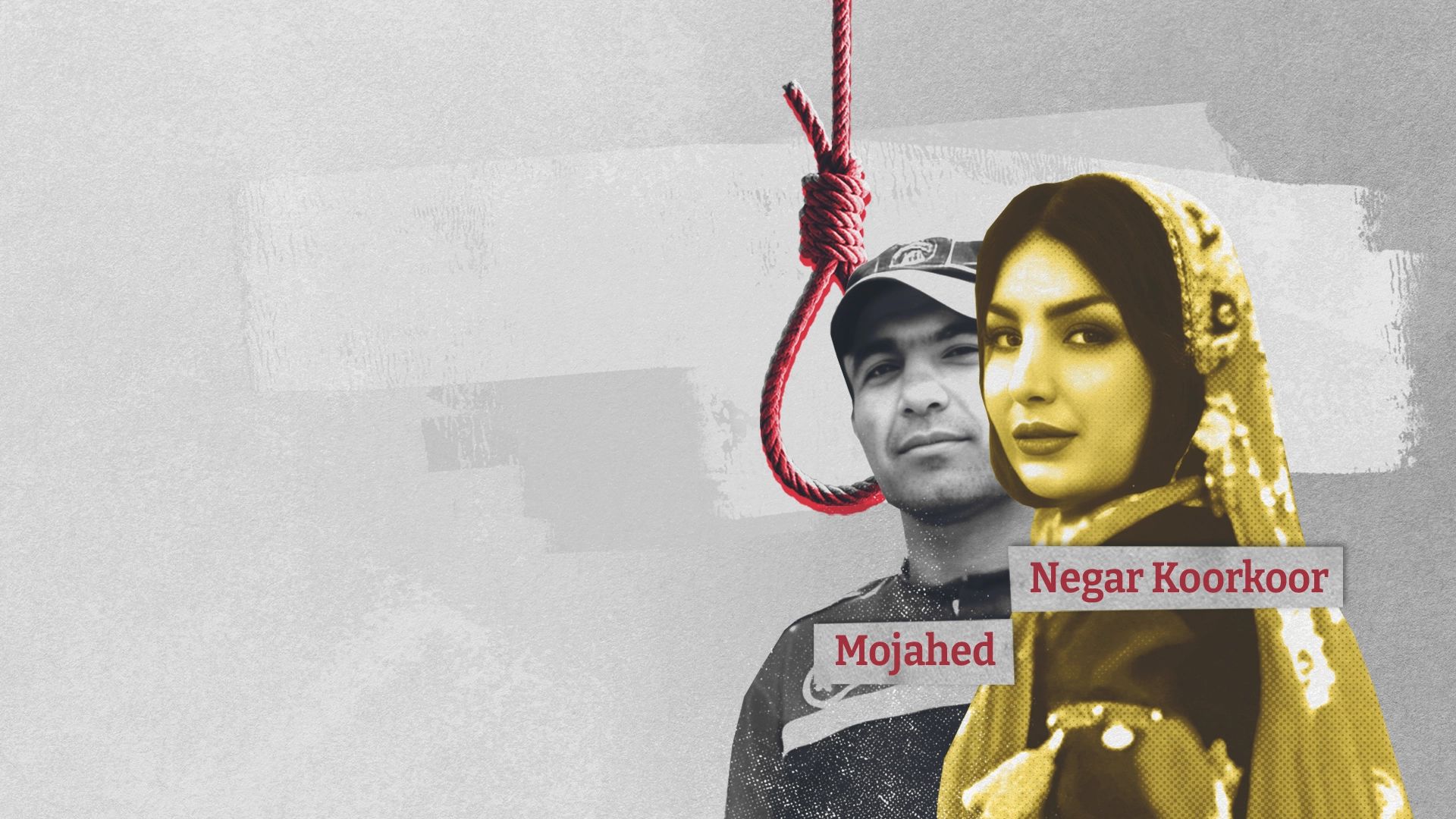

Many Iranians, whose loved ones were jailed or killed during the protests, have channeled their grief into human rights activism. Among them is 33-year-old Negar Koorkoor, who says she became an activist after her brother, Mojahed, was arrested on December 20, 2022, amid the protests—and later handed an arbitrary death sentence.

Desperate to save him, she turned to social media, hoping that raising public awareness would halt the execution. Instead, the attention—from the media and several US and European human rights groups—made her a direct target of Iranian security authorities.

Eventually, she says she had no choice but to flee. In June 2023, she crossed from Khoy in northwestern Iran into Turkey. “As I crossed the border, I kept thinking, ‘What if they arrest me?’ I was terrified,” she recalls. “If I was arrested too, who would be my brother’s voice?”

After her asylum application was denied, without a provided reason, she turned to off-the-books work—washing dishes and waitressing—to make ends meet, all while living in constant fear of being deported back to Iran. Thanks to the support of Iranian volunteer advocates, Koorkoor says she eventually secured a humanitarian visa and left Turkey.

She now lives in an undisclosed location in Germany, in refugee housing in a quiet town. Battling with gastrointestinal tumors, Koorkoor says she travels to another city for her treatment. Still determined to keep her brother's case in the spotlight, she hopes that increased attention from Western leaders on human rights in Iran will help prevent his execution.

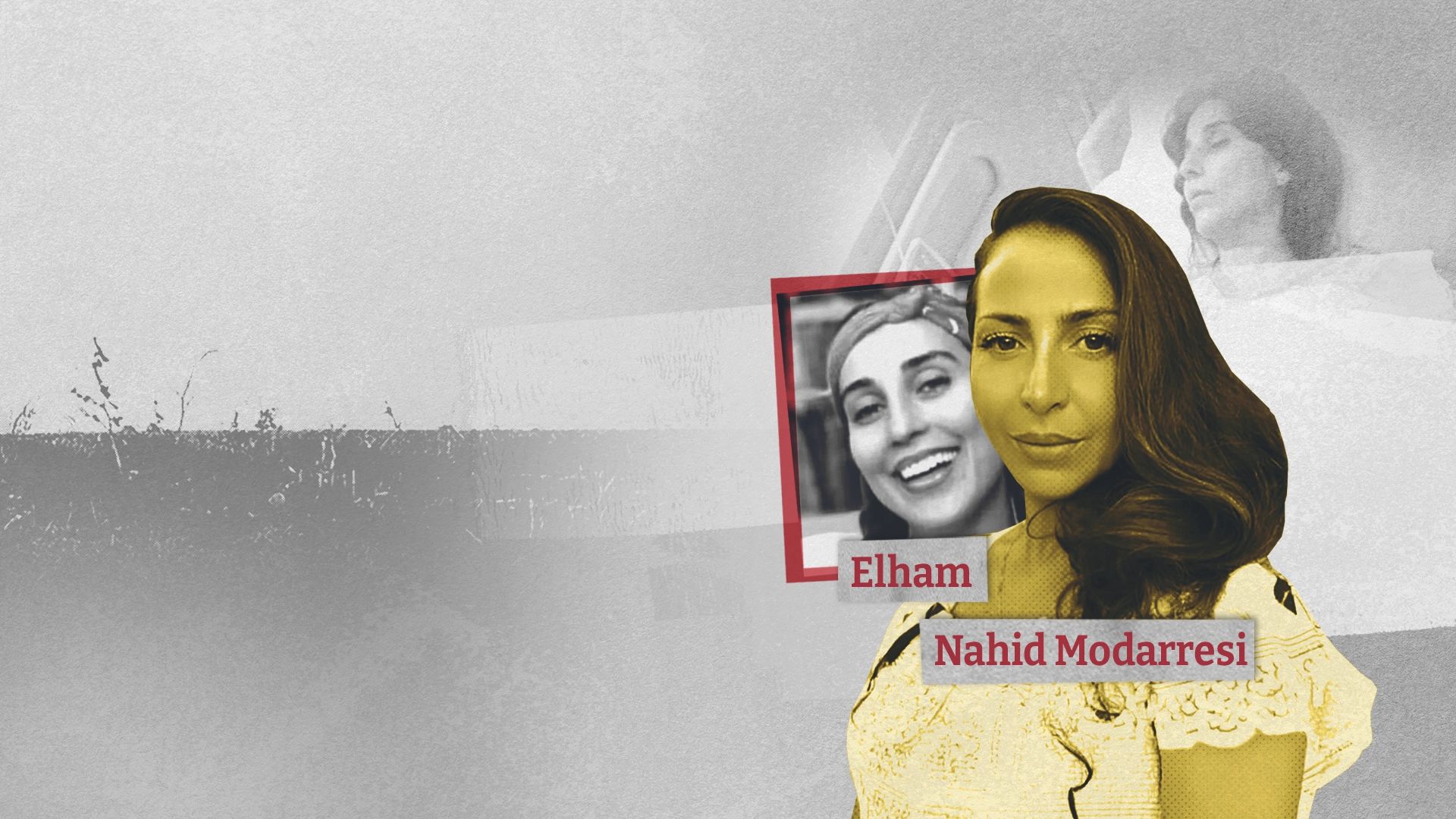

Similarly, 38-year-old Nahid Modaressi encountered threats from Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence after she began advocating for her sister, Elham Modaressi, who was arrested and tortured in November 2022.

“They called and threatened me, saying, ‘We will kill you in your sleep in ways you can't imagine'," she recalled one of the phone threats.

Modaressi, who left Iran several years before the protests, emerged as a vocal advocate for her sister’s release during the unrest and began speaking with independent media abroad. In what appears to be retaliation, the Iranian judiciary has since filed multiple charges against her—a development conveyed through her sister’s lawyer—including allegations of "working with hostile media" and "espionage."

Although she says her case was initially accepted by the UN in Turkey, documents show that Turkish immigration authorities eventually rejected it.

“When I appealed to the court, despite all the evidence showing my life is at risk in Iran, my case was rejected. I now live in constant stress and fear, worried that I will be handed over to the Islamic Republic," she said. "Being handed over to the regime means facing torture, imprisonment, and even execution.

Faced with the looming threat of deportation from Turkey—a fate that has often led to dissidents being jailed upon their return to Iran—Modaressi says she has only one option left. With help from Iranian-Canadian supporters, she submitted her refugee application before any deportation orders could be issued. Now she’s waiting for a decision under the Groups of Five (G5) program, a sponsorship route that typically takes over a year.

Several human rights groups are calling on Turkish authorities to stop the deportation and urging Canada to consider granting her the protection, they say she urgently needs.

Modaressi says she is hopeful that she will eventually be reunited with her sister Elham, who received asylum from Canada last year.

The fate of countless victims of the Iranian security forces’ crackdown also spurred Elnaz Bardiya to dedicate herself to advocacy—even from her base in Europe.

As a co-founder of the “My Share of Freedom” campaign, she works closely with dozens of families affected by the Woman, Life, Freedom movement to publicize their stories and raise funds for survivors and their loved ones.

“I fully understand and have lived through their pain, their fears, and their worries,” Bardiya says.

She says she could not remain indifferent to the struggles of dissidents in Iran, even at the risk of threats from Iranian authorities. “People my age, with similar worries and a common enemy, were being shot at—people who could have been my own brothers or sisters. If I were living in Iran, I might have been one of them. With this campaign, I tried to pay my share toward freedom,” she explains.

Bardiya says that many Iranian refugees must rely on personal connections or spend significant amounts on legal fees just to have their asylum applications considered.

Calling on Western leaders for substantial action to assist Iranian dissidents and refugees, she warns that “merely expressing concern will not save the lives of those at risk” and fails to help them reach safety in democratic countries.

Last November, an exhibition co-organized by Bardiya in Cologne, Germany—titled "Memories Left Behind"—paid tribute to the victims of 46 years of repression under the Islamic Republic. Family members of those killed present cautioned that the stories shared at the event only "scratched the surface" of the state's crimes.

"Iranians, too, are victims of war—war with the Islamic Republic; we, too, are enduring a slow death," Bardiya said.